An Awkward Look Back At The Excessive Makeup Trend Of The 2010s

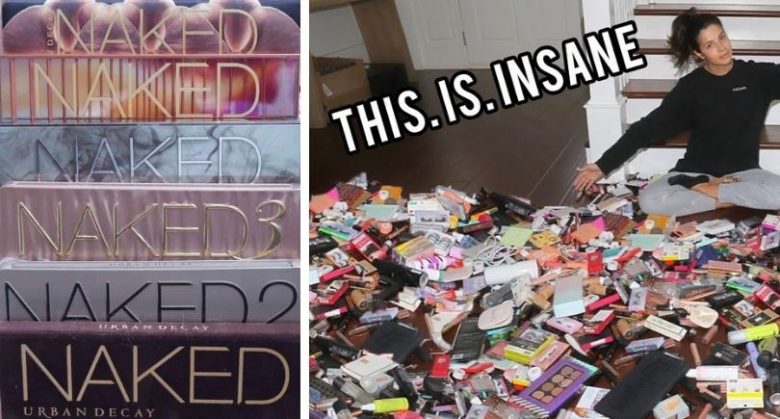

Beauty YouTuber Laura Lee (4.6m subscribers) is cleaning out her makeup collection. In the thumbnail of her three-part decluttering vlog, Laura sits on the floor surrounded by hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of barely-used products — she’s binning all of it.

Type “makeup decluttering” into YouTube and you’ll see similar scenes — sprawls of expired, barely-touched cosmetics that YouTubers are throwing away en masse. These hoards of makeup are the legacy of 2010s beauty culture: an era defined by sculpted eyebrows, Urban Decay’s Naked palette, and an overwhelming obsession with excess.

Via Laura Lee, YouTube

“I used to think I needed all this [makeup] because I watched so many beauty YouTubers with collections this big,” reads one of the top comments on Laura’s video. “But along the way, I realised we crave the thrill of buying/owning instead of the actual function of the products.”

Indeed, beauty YouTube had a chokehold over the entire internet. So much so, that it had all of us convinced that it was totally normal to stockpile enough makeup to paint the ceilings of the Sistine Chapel — let alone our faces. But how did it reach this point?

The Normalisation of Excess

Beauty content on YouTube mostly began as ‘how to’ tutorials. In the late ’00s, the platform consisted of hobbyists that recreated celebrity beauty looks, or helped demystify winged eyeliner for less makeup savvy audiences. But this soon changed.

The 2010s saw the rise of ‘hauls’ and ‘makeup collection tours’, which quickly dominated the beauty genre. Some of the most popular videos to date involve makeup collections that span entire rooms.

It became normal to hoard drawers full of eyeliners, even if most of the products expired in 6-12 months and couldn’t possibly all be used (even if you pulled a Julia Fox-inspired look every day). Shopping for countless products had taken centre stage and we were all transfixed. By 2014, beauty content was drawing in 700 million views per month on YouTube.

Via Christen Dominique, YouTube

The Dawn of the Influencer

Beauty YouTubers were some of the first influencers before the term even existed.

Michelle Phan (8.8m subscribers) was one of the first ever ‘beauty gurus’, making her debut in 2006 and exuding major big sister energy through lo-fi, grainy webcam recordings. As YouTube took off in the early 2010s, YouTubers including Zoella (4.9m subscribers), Carli Bybel (6.1m subscribers), and Kathleen Lights (4.1m subscribers) would become household names to teenage girls around the world.

Unlike traditional celebrities, YouTubers spoke directly to viewers: broadcasting from their bedrooms into ours. They shared their makeup routines while sharing details of their lives. They seemed affable, authentic, and above all, trustworthy. They (probably) didn’t know it initially, but this trustworthiness was a new form of currency that would soon become bankable by the millions.

Via Zoella, YouTube

YouTubers soon started pivoting from providing entertainment to pushing products. Once brands got wind of the influence that YouTubers held, advertising was interjected through sponsorships and affiliate links. These were highly lucrative incentives for YouTubers to promote products to their audiences, and the lack of advertising regulations in the early 2010s meant that these sponsorships were often undisclosed. The result was billions of minutes of beauty marketing being consumed — often without viewers even knowing that they were being advertised to.

YouTube viewers were also developing a deep level of personal investment in the beauty vloggers they subscribed to. Scarlett Curtis wrote in an 2014 article for The Guardian that YouTube celebrities like Zoella had helped her through her struggles with depression. There was a common sentiment that YouTubers felt like ‘friends’ — or, at least, someone we could theoretically be friends with. This made us all the more trusting when a YouTuber recommended a product they were ‘just sooooo obsessed’ with. And just like our friends shape our norms and habits, beauty YouTubers were creating new norms defined by a never-ending stream of products.

The Fallout

Naturally, when we watch influencers that we like, we want to emulate them. For many people, especially younger audiences, beauty YouTube was a gateway into a world of hyper-consumption. As YouTuber Jordan Theresa puts it in her video essay on the topic: “If something is put in your face enough, you’ll either want it or think that you need it.”

Reddit community r/MakeupRehab began in 2014 in response to the increasing consumer culture surrounding makeup and beauty. The community boasts over 100k members and provides a space for those who have struggled with consumerism, or those who oppose the crazy levels of consumption associated with being interested in cosmetics.

Guilt, shame and regret are common themes that emerge in the threads, as users discuss and come to terms with how much they spent while trapped in a toxic cycle of shopping. And what’s one of the most frequently cited triggers for excessive spending? Beauty content on YouTube.

Via The Fancy Face, YouTube

One user describes having a shopping addiction that was “fed by the onslaught of reviews, hauls, collection videos that are perpetually being uploaded to YouTube”. The user became aware of the problem she had with excessive consumption after going through her makeup collection during the pandemic. “It was a hard reality check for me. Thousands of dollars of unused or hardly touched products made me feel sick to look at. The craziest thing is — in this huge makeup obsession that I had — actually using the makeup wasn’t even a part of the cycle.”

The Downfall of Beauty Youtube

If authenticity and relatability were the currency that YouTubers traded in, then losing credibility could spell disaster. YouTubers went from recording in their bedrooms to broadcasting from mansions. Slowly, people began to realise how much money YouTubers were making through paid partnerships, casting doubts over whether these people were still trustworthy sources for beauty advice.

MannyMUA, LauraLee, James Charles, and now Jaclyn Hill—moral of the story is don’t trust all the popular rich ad/promo filled Youtubers. Show some love for the smaller, humble, honest AND talented beauty influencers out there who deserve so much more ?

— #BLM?⁷ (@ShyGuySinthia14) June 9, 2019

In addition, a series of controversies further chipped away at the trust people placed in YouTubers. Multiple YouTube personalities received major backlash for launching low-quality or overpriced products that were perceived as blatant cash grabs (i.e. Zoella’s £50 advent calendar that consisted of little more than a few cookie cutters and some confetti). YouTuber Jaclyn Hill even released a line of lipsticks that sparked safety concerns after multiple customers reported finding hair, bubbles, plastic, and even metal fragments in the products.

On the back of beauty YouTubers having to contend with waning trust from viewers and a slew of damaged reputations, a vibe shift was already taking place. Trend cycles were changing, and the pendulum was swinging toward more streamlined, minimal makeup routines. Cosmetic labels such as Glossier and Milk Makeup took over as the brands de jour, with a new minimalist aesthetic that embraced barely-there makeup for a (deceptively) effortless look.

Later dubbed ‘clean makeup’ (albeit, problematically), trendsetting celebrities such as Hailey Bieber epitomised the look with a signature combination of cream blush, fluffed brows, and dewy ‘glazed donut’ skin.

Via Hailey Bieber, Instagram

The Aftermath

Overconsumption is certainly not a problem purely relegated to the 2010s. Although haul videos dropped off in popularity by the end of the decade, the format is now experiencing a resurgence on TikTok. The difference is that we now have a much clearer understanding of the line between entertainment and advertisement, along with better regulation of sponsored content, and a greater awareness of our responsibility towards shopping sustainably.

Users in the subreddit r/MakeupRehab post about finally breaking free from the vicious cycle of buying makeup. They cite the importance of having self-compassion and self-forgiveness, in order to let go and create more sustainable habits in the future. As one user put it: “Sometimes we can get mad at our past selves for our purchasing mistakes and/or hoarding habits. But today, take a moment to forgive yourself… you’re already on the right path to being a better you.”

With any luck, excessive consumption is a 2010s trend that we can all leave behind for good.

–

Header via Feel Pretty With Pri/YouTube.